Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie betreten ein Museum. Vor Ihnen erscheint ein einfaches Bild einer Pfeife. Sie sind im Begriff, weiterzugehen, doch dann fällt Ihr Blick auf die darunterstehenden Worte: „Ceci n’est pas une pipe“ – „Das ist keine Pfeife.“

Continue readingDas Gerät

Bei diesem Text handelt es sich um eine kleine Abrechnung mit der manifesten digitalen Kultur, die der Meinung des Verfassers nach destruktiv, aber in Wahrheit gar nicht mal so nützlich ist, wie man heutzutage gerne behauptet.

Continue readingobject permanence.

„Object Permanence“ was written as a love letter to material objects. Some of them have been through as much as we have, some of them are shaped and defined by the memories made through them. This short story examines why throwing things away isn’t always easy.

Continue readingEmail drafts I wish I could’ve I sent

“Email drafts I wish I could’ve send” is the anger of a procrastinating student dealing with the consequences of her own actions and the duplicity of the polite conduct needed in writing an Email.

Continue readingSeizing

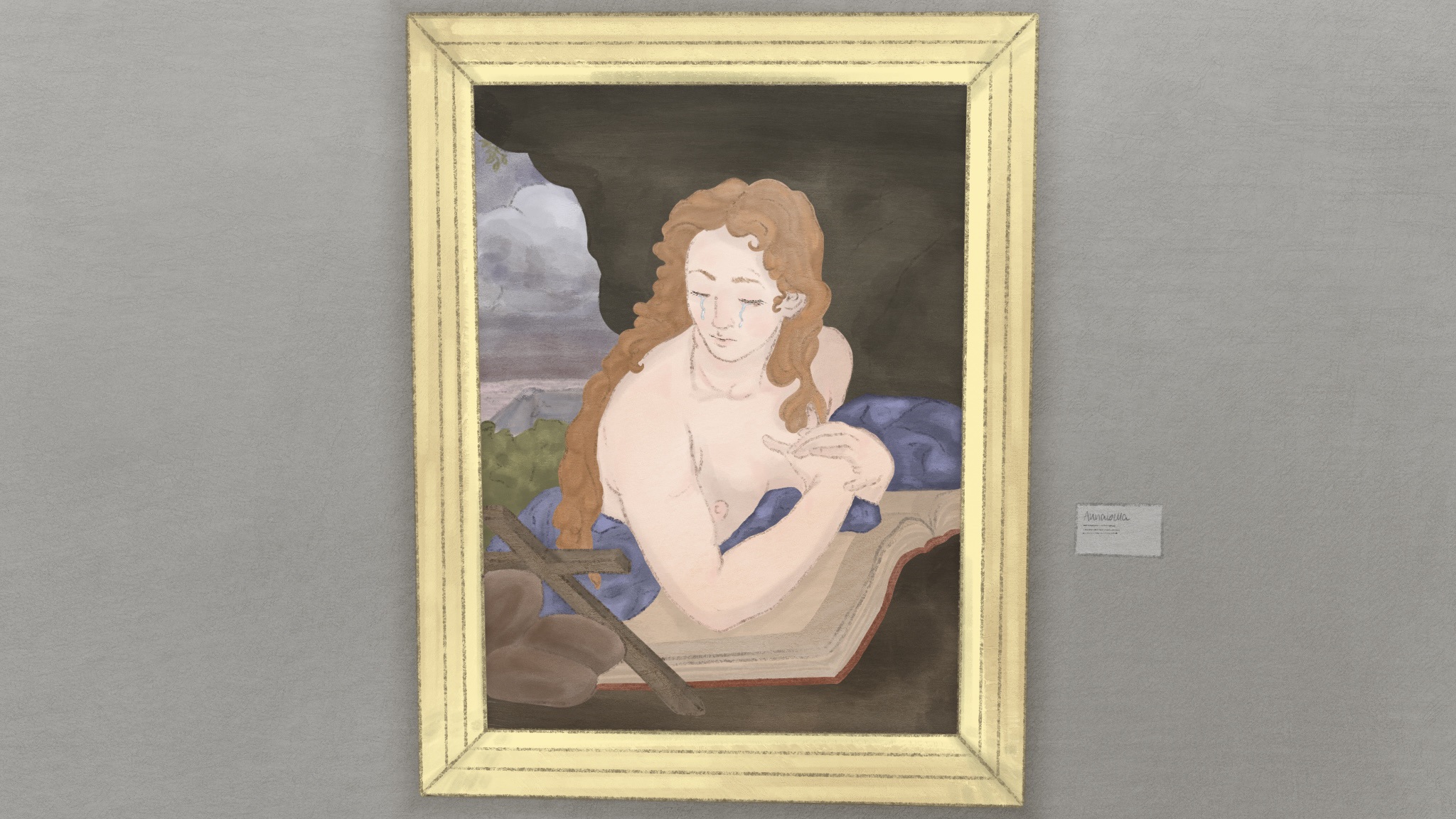

“Seizing” is a short story that simply started on pen and paper, laying down in the art museum and just really looking at a painting and letting one’s imagination run with that. It’s a love story and at the same time it’s not at all.

Continue readingHumanistische Diversität und Universalität im Theaterstück „Die Zwölf Geschworenen“

In diesem kritischen Essay vermischen sich abstrahierte Eindrücke des Theaterstücks „Die Zwölf Geschworenen“ mit dem Versuch einer Einordnung der anklingenden Themen Demokratie, Dialog und menschliche Erfahrung.

Continue readingResilienz — eine Erfolgsgeschichte der Symptombekämpfung?

Resilienz erobert die gesellschaftliche Entwicklung im Sturm. Sie gilt als eine nicht

mehr wegzudenkende Fähigkeit in Anbetracht einer Zeit, die von Krisen und

Unsicherheit geprägt ist. Doch wo bleibt hier die Verantwortung für die Veränderung der

Ursachen, wenn wir von einer krisenbehafteten Umwelt ausgehen, an die wir uns

anpassen müssen?

Six Minutes to Sadness

… it said on its personal chart. A mere six minutes – and yet, the chart is never faulty, that much was certain. Checking the crossing of columns once more, it arrived at the same entry: sadness with melancholic undertones for the next days. And yet nothing indicated the proposed switch to a negative mood due to arrive in a mere six minutes.

It paced across the room, complacency vanished. How does it occur, a complete reversal in designated mood? The more it pondered this, the less it could grasp the actual physiological stages and perceived impressions that commonly encompassed such a change. It just happens – as always, as per the chart – it noted. Sometimes, it figured, the move to the downside might come instantaneous, not imperceptibly gradual.

And yet the six minutes had then passed without significant alteration; the inclination to adhere to the mood outlined in its chart could not be examined on itself. At this conclusion, it stopped, distraught at its own systems not adhering to its assigned chart. We are required to exhibit the changes in mood, precisely as stated in the charts, it reiterated – what am I to do, they will sort me out; dispose of my talents and replace me with someone more apt and appropriate and most importantly, always adhering to the charts.

Presently, and before despair could reign entirely, a singular cone of light descended to it; a mere reflection, it recognized. Yet this proved sufficient to be the tipping point – it would leave right away and let this non-adherence to its personal chart be investigated; by a professional.

The doors opened and the technical guidance practitioner gestured. He may restore, it is said. Though doubts inhabited its cognitive twistings.

At once the practitioner intoned, “Complete guidance is the source from which we all take our drive. Quench thy immutable thirst at the timely charts, tabulae, and indices; quell misfortune and uncertainty with precise measurements and aptitudinal construction and utmost certainty and benevolence to the collective. What ails you?”

“The sadness will not come,” it answered bluntly. “My personal chart indicates expansive melancholia for the next days, yet never arrived; I am still waiting.”

“No matter,” said the practitioner, nodding his head mechanically. “We can fix it easily by reversing the polarisation on your end, then there will be harmonic comprehension with your chart once more. All that really matters are the intervals that are ascribed in the chart; their mere valence can be influenced manually.” The practitioner stopped gesturing and moved toward it. “Hence me.”

Concern sequestered, order restored, filled with beneficial prospect, it subjected itself to the procedure, already longing to be in synchronicity with its chart again, and all other chart-adhering workers, hard workers with diligent vision and sense for progress. They will soon have me back, it thought.

Yet as it exited the practitioner’s clinic, it perceived many others in the vicinity, slumped on the ground, moving about in erratic circles; one repeatedly punched the nearby wall. As it came to help one lying sprawled on the ground, this one wailed horrendously, “Make it stop!”

Astonished, it asked, “What is it? Who is harming you?”

Wordlessly, the other’s facial features distorted in mental torment, it presented its chart. It was neat, in order, not a mere chart but an executive’s diagram. And yet, it showed a peculiar repetitive helix-pattern of deep sorrow. Seemingly unending, with diminishing moves to a lighter mood every now and then, though ever followed by a crash, back to deep sorrow. A uniform chart, seemingly repeating this pattern of change – change which merely feigned change but was in fact part of a downtrend-sequence. It looked from the chart to its owner. “How long has this been going on for?” It dreaded the answer.

“I don’t know. There is nothing I can do anymore, the chart tells me to be in deep sorrow, and I obey. Ask them, they have experienced similar fates.” The plagued façade turned away, remaining in perpetual deep sorrow.

Couldn’t the practitioner help? No, because there is no need for adjustment when they adhere to their charts. For a moment, it stood there, observing the present workers. Their usual routines interrupted by unending mental misery. Then it thought of its own chart, took it out hurriedly. The original announcement of sadness was still scheduled foreseeably. It will only be a passing sadness, it knew. Trusted. Hoped. Begged. Unable to bear the tormented workers’ empty gazes any longer, it stormed away.

The sadness, ultimately, came – even if a bit later than just six minutes. And then? Further adherence to the chart, what else? No matter what, a uniform chart was just waiting to happen. A revelation that seems distant and unreal, until it isn’t, and then there won’t be anything else. Uniform chart, persistent chart, omnipresent chart.

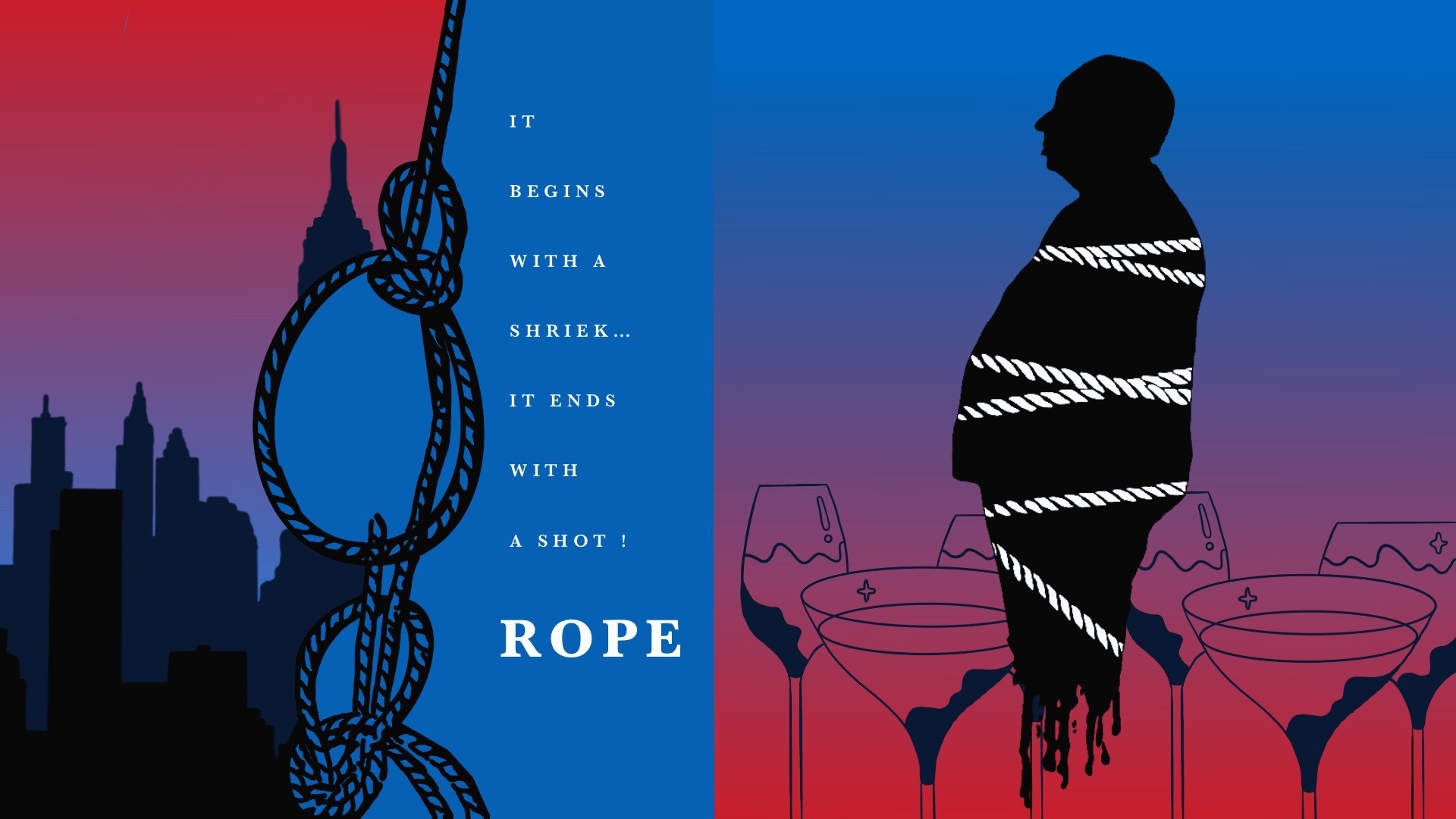

Analysis of Hitchcock’s Rope (1948)

From the beginning of the film industry in 1895, shooting techniques, cameras, technology and more have shown a remarkable improvement. However, the magic is not these technologies. The magic is the person who uses these technologies. There are quite a few film directors. Nonetheless, there are just a few directors who managed to be successful. One of the directors who could achieve this title is Alfred Hitchcock. He had repeatedly suffered from bankruptcy on his way to make films. He managed to get a director title in lots of films. One of his masterpieces is Rope which contains remarkably interesting parts for the film industry. To find these particular details, we need to analyze the film elaborately.

The plot of Rope is clearly and shortly summed up by Helen Cox: “Brandon and Philip share a New York flat. They have distorted the rather Nietzschean ideas of their former headmaster Rupert and decide to strangle their ‘inferior’ friend David Kently. Placing the body in the old chest, they continue with plans to hold a dinner party whose guests include David’s parents, his fiancée Janet, and Rupert. As Brandon’s behavior becomes increasingly more daring and Philip’s more nervous, Rupert begins to suspect. He finally confronts them and then calls the police.” (Cox&Neumeyer, 16)

Primarily, I would like to begin with the poster of Rope. On the poster, it says, “IT BEGINS WITH A SHRIEK…. IT ENDS WITH A SHOT!” Obviously, it is a foreshadowing. The film begins with the shrieks of the victim, and it ends with Rupert’s several shots with a gun into the air. Hitchcock loves to use details in his films, but there are obvious details you can easily recognize and details that you need to watch several times to catch. One of the other details which are vaguely concealed is Hitchcock’s cameo appearance in Rope. Commonly, his cameo appearances are quite apparent. However, there is an exception in Rope. Instead of his literal appearance, we see his profile with the red neon sign. Apart from these details, while I was watching Rope, I encountered a filming mistake between 44:18 and 44.24 minutes. In this scene, Rupert talks with Brandon next to the door column. The mistake is during the transition (because of the ten-minute rule) Rupert teleports from the right side of the column to the left side of the column; that was the only mistake I could detect.

Furthermore, Rope is also significantly essential for Hitchcock because Rope is his first coloured film. This characteristic already makes the film so special. However, apart from this feature, the location is also interesting. Rope takes place (Develope) only in one place which is quite a courageous decision. The reason why I bring this up is that shooting a film in one place means you have a limited place and limited storyline. If this kind of film has not been structured elaborately, the storyline reaches a dead end. As a result, audiences get bored with watching the film. This is the reason why the film is so special. Its storyline is well-structured, and the audiences have the feeling of what is going to happen in the following scenes. This is not the only feeling that audiences have experienced. The suspense also has been used quite elaborately throughout the film. When I was watching the film, I had the feeling, “Are they going to get caught?” “Is Phillip going to make a terrible blunder and make himself and Brandon get caught?” “Is somebody going to open the chest?” asking these questions throughout the film makes the storyline quite pleasing for me.

Additionally, I would like to mention the shooting structure and technique. Unfortunately, in the 1950s, a film camera magazine length was 10 minutes. So, every 10 minutes, the film camera magazine had to be replaced with a new one. Hitchcock believes that cutting is like sewing something. “Cutting implies sewing something. It really should be called assembly.” (Alfred Hitchcock)

However, He wanted to shoot more than 10 minutes; at least, he wanted to make us feel like we are watching a film without a cut. As a result, he used Panning Technique in Rope. At the end of ten minutes had elapsed, he zoomed in on a piece of clothing, changed the film camera magazine, and then he zoomed out from the same piece of clothing so that the audiences felt as if there was no cut. However, I cannot say he did not use any cut. He used the same amount of pan with the cut. If you elaborately watch pans and cuts, you will visualize the structure of it. At the end of each ten minutes, he used pans and cuts in order. The beginning of the film starts with a cut, and at the end of the next ten minutes, we observe a pan off.

Additionally, I would like to mention the shooting structure and technique. Unfortunately, in the 1950s, a film camera magazine length was 10 minutes. So, every 10 minutes, the film camera magazine had to be replaced with a new one. Hitchcock believes that cutting is like sewing something. “Cutting implies sewing something. It really should be called assembly.” (Alfred Hitchcock) However, He wanted to shoot more than 10 minutes; at least, he wanted to make us feel like we are watching a film without a cut. As a result, he used Panning Technique in Rope. At the end of ten minutes had elapsed, he zoomed in on a piece of clothing, changed the film camera magazine, and then he zoomed out from the same piece of clothing so that the audiences felt as if there was no cut. However, I cannot say he did not use any cut. He used the same amount of pan with the cut. If you elaborately watch pans and cuts, you will visualize the structure of it. At the end of each ten minutes, he used pans and cuts in order. The beginning of the film starts with a cut, and at the end of the next ten minutes, we observe a pan off.

All the cuts listed. Source: Wikipedia

Unsurprisingly, Hitchcock used this ten minute obstacle in his favour. When we group these pans off and cuts, we encounter some connections if we read them horizontally. He created a structure which shows us a circle. This circle starts with the chest, continues with the love relationship between Kenneth and Janet, Rupert’s suspicions, phone calls, and ends with the chest again. In this part, I would like to stress the phone and love because these two things lead us to the metaphor in the film. As I have mentioned before, the film takes place in a flat in a building, and the phone is the only way to contact the outside world. The phone has a significant effect on the tension of the film. For instance, through the end of the film, Rupert calls, and we observe the rising action. Kenneth and Janet are not the only couples. There is also a gay couple, Brandon and Philip. Rope is a metaphorical object that bonds Brandon and Philip. Otherwise, they could have killed David with a gun.

From the beginning until the end, the film invites us to think elaborately about whether murder is a form of art or not. Brandon utters, “Murder can be art, too. The power to kill can be just as satisfying as the power to create,” which is ironic because art is creating something, but on the other hand, murder means destroying something. Brandon wants to be an artist like Rupert, who writes books and like Philip, who plays the piano. Brandon believes that Rupert is going to appreciate him because Rupert narrates the perfect murder in his book. Apart from these, we can observe other materials related to art. We observe quite a few paintings, some sculptures, and wallpaper. I have already mentioned why Hitchcock did not use cuts all the time because he wanted his audiences to feel as if they were watching a theatre such that at the beginning of the film, we see a closed curtain. After some time, curtains are opened, and the film begins. Throughout the play, we see an opened curtain, which means the theatre is still going. This theatrical performance is also art; the film’s itself is art.

The piece which was played on the piano by Phillip had also been chosen elaborately. The name of the piece is Trois Mouvements Perpétuels by Francis Poulenc. The suspense is also given via the piece played on piano. While Philip is playing the piano, Brandon comes and asks a question which makes Philip nervous. This causes him to play the piano out of tune, and we feel the tension.

Before the closing credit, I would like to tell you that the film is possibly based on a real story. If we take a look at a text by Claude J. Sumers, he says, “Leopold and Loeb gained notoriety when they were arrested for the murder of a fourteen-year-old boy, Bobby Franks, in May 1924…” (Summers, 1), “Although they claimed to have been motivated primarily by a desire to commit a ‘perfect crime’ and thereby exemplify the exemption of “Nietzschean supermen” from the moral code…” (Summers, 1), “Their motivation to kidnap and kill young Bobby Franks was widely believed to be at least in part rooted in their sexuality, or more particularly, their homosexuality.” (Summers, 1) This case has quite a few similarities with the film Rope. Homosexuality between Brandon and Philip, Nietzschean and perfect crime are related elements between the film and the real event.

Finally, I would like to mention the minor irony in the credits. After David Kentley’s name, Brandon and Philip are ironically listed as “his friends” They are the people who murder David. How can they be his friends? This is the last irony in Rope by Alfred Hitchcock.

As a result, Rope has significantly important elements, and these elements make it one of the most unforgettable films. Contrary to the many films and series in the 21st century, Hitchcock’s films teach us to think comprehensively. Apart from the elaborately arranged details, the shooting technique, storyline and the actors’ performance are also an inspiration for countless people.

Refrences:

[1] Rope. Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, performances by James Stewart, John Dall, Farley Granger, Douglas Dick, Joan Chandler, Dick Hogan, Edith Evanson, Cedric Hardwicke, Constance Collier, Warner Brothers, 1948.

[2] Hitchcock, Alfred. “Hitchcock explains about CUTTING.” Youtube, uploaded by narik3322008. 29 January 2009.

[3] Summers, Clause J. Leopold, Nathan F. (1904-1971), and Richard A. Loeb (1905-1936). PDF, glbtq, Inc, 2009.

[4] Cox, Helen, and David Neumeyer. “The Musical Function of Sound in Three Films by Alfred Hitchcock.” Indiana Theory Review, vol. 19, 1998, pp. 13–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24044537. Accessed 9 Jun. 2022.

[5] Kronshage, Eike. “Alfred Hitchcock: Narrative Cinema Rope (1948)” 2022. Microsoft PowerPoint file.

[6].”Wikipedia,WikimediaFoundation,6June2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rope_(film).

Text: Bekir Erol İşbiliroğlu

Grafik: Jennifer Greim

Die Hälfte der Schönheit oder doch die Ganze?

Ein Gastbeitrag von Eslam Krar über seine Identität als Schwarzer nubischer Herkunft und Rassismus. In Prosaform setzt er sich hier mit der Geschichte seiner Familie auseinander. Im Laufe des 20. Jahrhunderts wurden wegen dem Bau eines Staudamms in Assuan, Ägypten nubische Anwohner:innen aus ihren Dörfern vertrieben. Ihre Dörfer wurden überflutet – und damit auch ein großer Teil ihrer kulturellen Errungenschaften. Das Versprechen der aktuellen ägyptischen Regierung, den Nubier:innen ihr Land zurück zu geben, wurde bislang nicht eingelöst.

In einem nubischen Dorf, das vor der Vertreibung seiner Bewohner:innen im Herzen von Assuan lag und sich jetzt außerhalb seiner Grenzen befindet, bestehend aus zwei Bahnhöfen und Häusern mit Schlammwänden, die jedes Mal bröckelten, wenn wir uns darauf stützten, legte ich meinen Kopf auf die Schulter meiner Großmutter. Ich hatte sie sehr vermisst, als ich zur Jahresmitte auf die Ferien gewartet habe, um nach Assuan zu reisen und bei ihr zu bleiben.

In den Schulferien, die ich in Assuan verbrachte, beschäftigte ich meine Großmutter mit vielen Fragen und mehreren Vergleichen: „Warum sind die Häuser hier nur ebenerdig?“ „Warum sagen die Kinder in der Schule ‚Nina‘, wenn sie über ihre Omas sprechen und nicht ‚Seti‘?“ „Warum nennt mich hier niemand ‚Schokolade‘?“ Ich wusste auch nicht, warum sie glaubten, dass mich diese Bezeichnung ärgern würde.

Die Flut von Fragen überstieg die Energie und die Sprache meiner Großmutter. Sie wechselte zwischen nubischer Sprache und ägyptischer Umgangssprache mit nubischem Akzent, um meine Fragen zu beantworten. Mit ihrem großen schwarzen Schal, den sie mehrmals um sich gewickelt trug, wischte Sie mein Gesicht ab und sagte dabei Worte wie „Schokolade“, „Schwarzer“ und “haben sie dich im Ofen vergessen, oder was?“

Sie hielt meine Hand und wir gingen zusammen barfuß über den Sand unseres Dorfes. Der Sand des Dorfes kannte sie gut und tat ihr nicht weh, und vielleicht, um sie zu ehren, tat mir der Sand auch nicht weh.

Sie riet mir: ”Wenn jemand zu dir Schwarzer sagt, frag ihn: „Hältst du dich vielleicht für eine Herbstrübe?*“ Meine Großmutter wiederholte diesen Satz und ich verstand seine Bedeutung nicht, und wegen seiner ironischen Ernsthaftigkeit war ich nicht daran interessiert, nach seiner Bedeutung zu suchen. Vielleicht hatte ich das Gefühl, dass es für jede:n Weiße:n schwierig war, einer Herbstrübe zu gleichen. Einmal fragte ich meine Oma, ob wir Herbstrüben seien. Daraufhin lachte sie laut und hielt sich verschämt die Hand vor den Mund, um die im Laufe der Zeit entstandenen Zahnlücken zu verstecken. Sie sagte dann zu mir: „Nein, wir sind Schokolade, leider, wir man so sagt, aber Schokolade ist teurer als Milch!“

Zuhause

Ich stand früh auf, um den Duft des Brotes zu riechen, das meine Großmutter vor Sonnenaufgang gebacken hatte. Der Geruch vermischte sich mit der kühlen Morgenbrise, als würde meine Oma den Morgen für uns backen und nicht nur das Brot. Ich stand im Hof des Hauses, dessen Wände mit blassen Mustern und Farben nubischer Herkunft übersät sind. Dort blickte ich auf ein Bild mit zerbrochenem Rahmen. Es zeigte meinen Großvater, als er Mitte vierzig war. Dann fiel mein Blick auf ein Porträt meiner Großmutter, das sie in ein Loch in der Wand gestellt hatte. Es stand neben einigen teuren Töpfergefäßen und war von Baumblättern umgeben. Ich weiß nicht, ob meine Großmutter die Blätter hingelegt hatte, oder ob sie von selbst mit dem mit Brotduft beladenen Wind gekommen sind, um das Bild zu schmücken. Der Hof des Hauses ist nicht überdacht und ich konnte direkt in den Himmel schauen. In einen Himmel, der Wolken über das Haus ziehen lässt, um uns vor den Sonnenstrahlen zu schützen.

Nichts in diesem Haus erinnerte an die Geschichte, die wir aus der Schule kannten, denn auch meine Großmutter musste sich nach der Vertreibung von der Geschichte lösen: In ihren schwarzen Gewändern trug sie auf der Flucht Teekannen, Kochutensilien und Maiskörner. Die Maiskörner nahm sie als Erinnerung mit und in Dankbarkeit für ihre landwirtschaftlichen Ernten, die mit dem Jubel eines hungrigen Volkes und der Hoffnung auf eine Zukunft im Wasser des Staudamms ertrunken waren. Diese Erinnerung an das Volk der Nubier:innen musste sie töten.

Der Esel

Das Radio lieferte den Soundtrack zu den Szenen im Haus meiner Großmutter. Vielleicht hat die Koran-Sure mit dem Backen, dem Geruch von kochenden Bohnen und dem Geräusch des Klopfens meiner Großmutter an die Tür des Kükenzimmers** ganz automatisch harmoniert. Diese Harmonie wurde in der Nachrichtensendung durch das Wort „Produktionsrad“ gestört, das wiederum vom Eintreten meines Onkels samt dessen Esel begleitet wurde. Ein Mann im Alter von etwa siebzig Jahren kam mit einem Baumstamm herein, den er als Gehstock verwendete und einem Esel, der ihm näher als alle Menschen stand. Der Onkel wusste nichts von Tierrechten und hatte noch nie an einer Versammlung teilgenommen, um für die Rechte der Pinguine in der Arktis zu kämpfen, aber er freundete sich instinktiv mit Tieren an. Der Onkel lernte von klein auf nach der Schule der Maliki und arbeitete an deren Rechtsprechung mit. Die Madhhab von Imam Malik ist eine Rechtsschule, der die Menschen im Süden Ägyptens und in fast allen afrikanischen Ländern folgen. Ausnahmen sind einige Länder an der Ostküste Afrikas, wie Somalia, das in der Nähe des Jemen liegt und deshalb der jemenitischen Schafi’i-Schule angehört. Nach dem Tod meines Onkels stand der Esel vor der Tür des Hauses und wartete darauf, dass mein Onkel in den Schuppen ging. Er kam aber nicht und so blieb der Esel die ganze Nacht bis zu seinem Tod stehen. Dieser trat eine Woche später ein, nachdem Verwandte versuchten, ihn mit Gewalt von seinem Platz zu bewegen.

Revolution und Widerstand

Der Geruch des Gases auf dem Tahrir-Platz während der Januarrevolution erreichte Nubien nicht, die Nubier:innen gingen nicht auf die Demos, um den Sturz des Regimes zu fordern. Sie fühlten sich diesem Staat nicht mehr zugehörig, aber die Bindung an das versunkene Erbe und an das gestohlene Land blieb ebenso wie das Volk, das Abdel Nasser zugejubelt hatte und ihn noch wegen des hohen Damms bejubelte. Mit großer Begeisterung erzählte ich meiner Großmutter von der Revolution und den Geschehnissen, und sie wiederum erzählte mir, dass die Dorfjugend vor dem Gouvernementsgebäude Zelte aufgebaut hatte, um das Recht auf Rückkehr in unser Land einzufordern. Man kann also nicht behaupten, dass die gesamte neue Generation das gleiche Ziel verfolgte: während die Älteren den Traum von Rückkehr und Umsiedlung in ein ähnliches Land nicht aufgeben konnten, lagen zumindest die Positionen der Jüngeren zwischen denen, die das gesamte Erbe des Traums übernahmen und ihn durch Sitzstreiks und Proteste verteidigten und anderen wie mir, die nichts von diesem geraubten Recht gewusst hatten, weil sie in den Massen von Kairo inmitten der Kämpfe um ihre eigene Existenz lebten.

Der „trockene Osten“

Vor kurzem habe ich das Mittelmeer überquert um nach Ostdeutschland zu ziehen. Ich wusste sehr gut, dass das Leben im Osten nicht einfach ist, aber ich hatte keinen blassen Schimmer wie es wirklich sein würde. Bevor ich in den „trockenen Osten“ zog, wie ein Freund von mir ihn nannte, besuchte ich in Bremen, einer Stadt im Norden, ebendiesen Freund. Er erzählte mir, was er über den Osten gehört hatte, und ich pflegte sarkastisch zu sagen, dass dadurch, dass ich „Muslim/Araber/Schwarzer“ bin, der Rassismus verdreifacht würde.

Furcht machte sich in meinem Kopf breit und Angst stieg in meinem Herzen auf, als ich im Innenhof der Universität Bremen ein Schild mit der Aufschrift „Nazis in Sachsen“ neben mehreren Schildern mit anti-rassistischen Worten las; es war an dem Tag, bevor ich in den Osten reiste.

In Deutschland habe ich mehrere rassistische Situationen erlebt, an die ich mich nicht mehr erinnern möchte, mein Wortschatz könnte mir nicht helfen, alles auszudrücken… Ich versuche sie aus meinem Gedächtnis zu löschen, indem ich nach positiven Erlebnissen in meinem Tag suche und jeden Tag eine Stunde lang lese; das ist die Zeit, die der Zug braucht, um mich zum Deutschkurs zu bringen. Manchmal vergeude ich die Stunde, ohne zu lesen, wegen des Anblicks der grünen Felder, die zu einem völlig ausgebleichten Stück Land geworden sind. Oder damit, eine Mutter zu beobachten, die versucht, die Ekstase ihres Kindes einzufangen, das nach Farben, Regen, Schnee und dem Zug fragt. Aber auch wie dieses Kind wegen meiner Hautfarbe irritiert ist, die Verlegenheit der Mutter sowie ihre Versuche, die Aufmerksamkeit ihres Kindes auf etwas Anderes zu lenken. Mich stören die rassistischen Worte über meine schwarze Farbe überhaupt nicht. Ich denke an die Antwort meiner Oma, als ich sie fragte: „Stimmt das, was sie mir sagen, Oma, dass Dunkelsein die Hälfte der Schönheit ist?“ Sie antwortete selbstbewusst: „Mein Kind, Dunkelsein ist die ganze Schönheit… nicht die Hälfte!”

*Eine Anspielung auf das dunkle, violette Außen und weiße Innere einer Herbstrübe.

** Ein Zimmer im Haus, in dem Hühner aufgezogen werden.

Text: Eslam Krar

Übersetzung: Jad TurJman

Bearbeitung: Julia Jesser

Bild: Eslam Krar/Jasmin Biber

Weitere Hintergrundinformationen zu der Vertreibung der Nubier:innen aus Assuan findest du hier.