„Object Permanence“ was written as a love letter to material objects. Some of them have been through as much as we have, some of them are shaped and defined by the memories made through them. This short story examines why throwing things away isn’t always easy.

Continue readingEmail drafts I wish I could’ve I sent

“Email drafts I wish I could’ve send” is the anger of a procrastinating student dealing with the consequences of her own actions and the duplicity of the polite conduct needed in writing an Email.

Continue readingSeizing

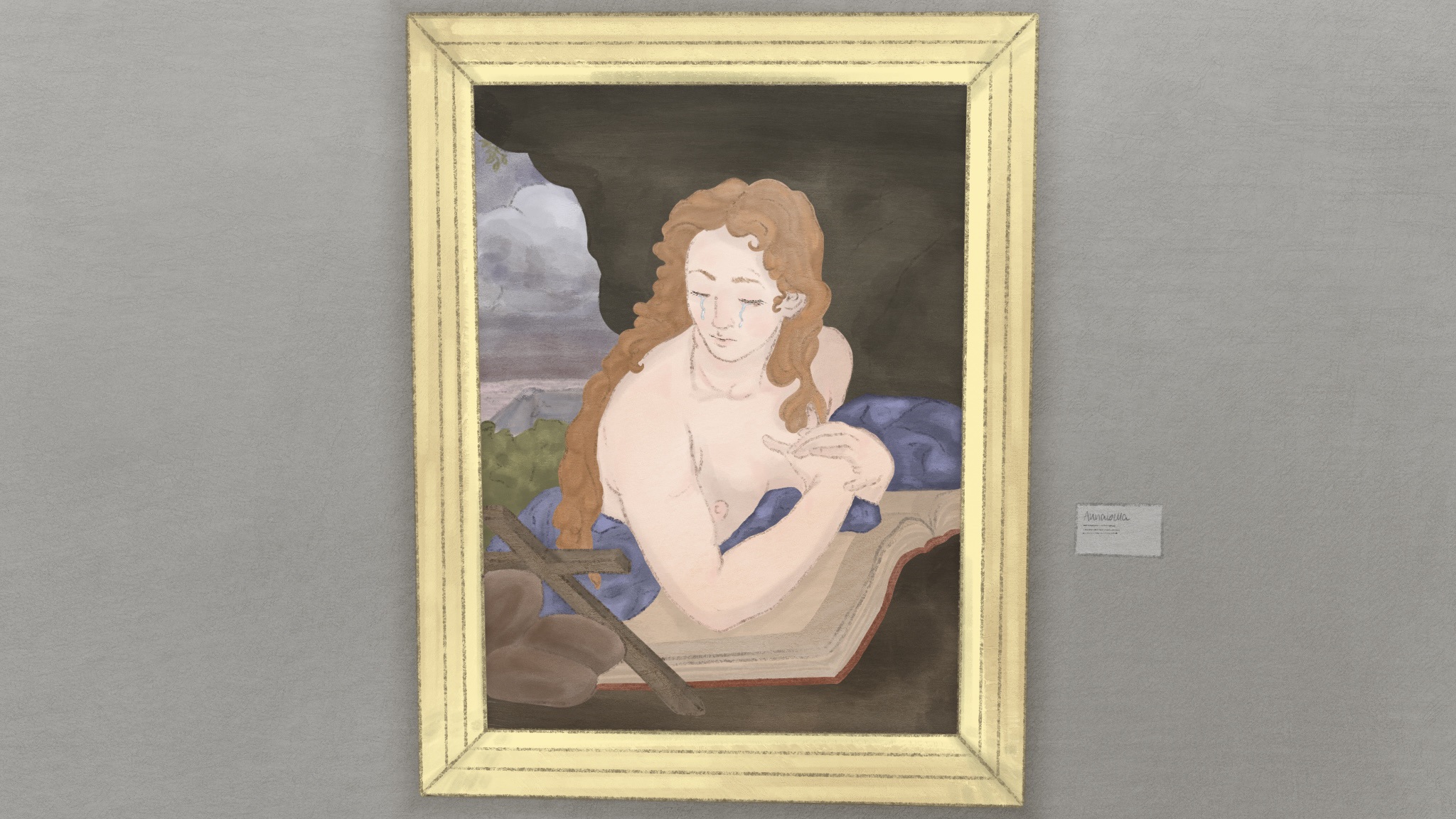

“Seizing” is a short story that simply started on pen and paper, laying down in the art museum and just really looking at a painting and letting one’s imagination run with that. It’s a love story and at the same time it’s not at all.

Continue readingDie Kandidat*innen für die Senatswahl 2023

Die Senatswahl 2023 der TU Chemnitz steht bevor. Damit ihr wisst wen ihr da überhaupt wählen könnt haben wir die einzelnen Listen gebeten sich vorzustellen und zeigen euch hier die Antworten.

Ihr wisst noch nicht worum es bei der kommenden Wahl geht? Hier haben wir euch eine Übersicht mit den zu wählenden Ämtern zusammengestellt.

1. Wahlvorschlag – TUCunited

1. Lehre und Studium an den aktuellen Standard anpassen: Mit der Gesetzesänderung im Frühjahr dieses Jahres hat der Gesetzgeber den sächsischen Hochschulen neue Möglichkeiten an die Hand gegeben. Aus unserer Sicht ist jetzt das Ziel, die Studienbedingungen an der TU Chemnitz durch eine Rahmenstudien- und -prüfungsordnung anzugleichen und dadurch auch die Studierbarkeit allgemein zu verbessern. Die Umsetzung soll partizipativ mit allen Verantwortlichen der Hochschule geschehen. Dabei sollen auch positive Erfahrungen aus den Digitalsemestern Einzug in reformierte Studiengänge finden.

2. Zielstrebige Umsetzung für eine nachhaltige Universität: Grundsätzlich hat sich sowohl das Rektorat als auch der Senat schon auf den Weg gemacht, die Universität nachhaltiger zu gestalten. Dennoch müssen diese Bemühungen konsequent umgesetzt werden. Klimaschutz muss einer der zentralen Entscheidungskriterien aller Gremien werden, insbesondere im Senat.

3. Bunte und offene Hochschule – klare Kante gegen Rassismus und Diskriminierung: Rassismus und Diskriminierung dürfen an unserer Hochschule keinen Platz haben. Dies gilt auch auch insbesondere für Gremienbesetzungen, die durch den Senat durchgeführt werden. Hier werden wir jede_n Kandidat_in genau unter die Lupe nehmen und uns gegen Personen stellen, deren Positionen unsere offene und von Akzeptanz geprägte Universität bedrohen. Wir sind bunt und das muss auch so bleiben, dafür stehen wir als studentische Vertretung im Senat. Diskriminierung ist keine Meinung!

Das sind die Kandidat*innen für den Senat:

Daniel Poguntke: An meiner Universität möchte ich gerne studieren und auch Kultur genießen. Genau ein solcher Ort soll die Universität für alle sein. Die Kulturhauptstadt ist eine hervorragende Möglichkeit für die Universität, ihr buntes und diverses Profil zu zeigen. Außerdem soll die Universität die Akkreditierung ihrer Studiengänge weiter konsequent verfolgen, um u. a. eine angemessene Prüfungslast zu erreichen. So ist auch mehr Zeit für eine lebhafte Campuskultur 😉

Marius Hirschfeld: Der Senat hat leider nur noch wenig Einfluss auf die Gestaltung eines konkreten Studiengangs. Umso wichtiger ist es, dass wir in der neuen Rahmenstudien- und -prüfungsordnung studifreundliche Regelungen durchsetzen, die dann auch für alle gelten. Das sehe ich als unsere größte Aufgabe an. Außerdem werde ich wieder einen genauen Blick auf alle Personen werfen, die vom Senat in diverse Gremien gesetzt werden. Dabei stelle ich mich gegen Personen, die nicht für eine bunte und offene Hochschule stehen.

***English Version***

1. Adapt teaching and study programmes to current standards: With the amendment to the law in the spring of this year, the legislator has given the Saxon universities new possibilities. From our point of view, the aim now is to harmonize the study conditions at Chemnitz University of Technology by means of framework study and examination regulations, thereby also improving studyability in general. The implementation should be carried out in a participatory manner with all those responsible at the university. Positive experiences from the digital semesters should also be incorporated into reformed degree programs.

2. Purposeful implementation for a sustainable university: In principle, both the Rectorate and the Senate have already set out to make the university more sustainable. Nevertheless, these efforts must be implemented consistently. Climate protection must become one of the central decision-making criteria for all committees, especially in the Senate.

3. Colorful and open university – Clear edge against racism and discrimination: Racism and discrimination must have no place at our university. This especially applies to the appointment of committees by the Senate. Here we will scrutinize every candidate and take a stand against persons whose positions threaten our open and accepting university. We are colorful and we must remain that way, that is what we stand for as student representatives in the Senate. Discrimination is not an opinion!

These are the candidates for the Senate:

Daniel Poguntke: I would like to study and also enjoy culture at my university. The university should be such a place for everyone. The Capital of Culture is an excellent opportunity for the university to showcase its colorful and diverse profile. In addition, the university should continue to consistently pursue the accreditation of its degree programs in order to achieve an appropriate exam load, among other things. This also leaves more time for a lively campus culture 😉

Marius Hirschfeld: Unfortunately, the Senate has little influence on the design of a specific degree program. This makes it all the more important that we enforce study-friendly regulations in the new framework study and exam regulations, which then also apply to everyone. I see this as our biggest task. I will also take another close look at all the people who are appointed to various committees by the Senate. In doing so, I will oppose people who do not stand for a diverse and open university.

2. Wahlvorschlag – Die beste Liste

Liebe Mitstudierende,

wir kandidieren als studentische Vertreter für den Senat der TU Chemnitz, weil wir eure Interessen gegenüber der Uni optimal vertreten wollen. Als Studierende haben wir eine einzigartige Perspektive auf die Herausforderungen und Chancen, denen wir an unserer Universität gegenüberstehen.

Das ist uns besonders wichtig:

1. Digitalisierung:

Um die in der Pandemie gewonnenen digitalen Strukturen auch weiterhin ideal nutzen zu können, ist die Bereitstellung von entsprechender Hardware für Prüfungen, Vorlesungen, Seminare, Meetings und Gruppenarbeiten essentiell. Darüber hinaus setzen wir uns für die Beschaffung von Lizenzen für studienrelevante Software ein, um ein optimales akademisches Arbeiten zu ermöglichen.

2. Studentisches Engagement stärken:

Da die Uni vom studentischen Engagement lebt, ist es unser Bestreben dieses Ehrenamt durch mehr Wertschätzung stärker zu honorieren und euch somit für die Gremienarbeit an der Hochschule (für eure Interessen), ob in StuRa, FSRä, Kommissionen aller Art, etc., zu gewinnen.

3. Transparenz und Kommunikation:

Wir streben eine transparente Kommunikation im Senat auf Augenhöhe an, um euren Interessen im Gremium Gehör zu verschaffen.

4. Studienbedingungen verbessern:

Es ist uns wichtig, dass die Studienbedingungen an der TU Chemnitz den höchsten Qualitätsstandards entsprechen. Wir werden uns dafür einsetzen, dass die Infrastruktur und die digitalen Ressourcen ständig verbessert werden.

5. Vielfalt und Inklusion:

Jeder sollte die Möglichkeit haben, an unserer Universität erfolgreich studieren zu können. Wir werden uns für eine diversitätsbewusste Hochschule einsetzen, die allen Studierenden Chancengleichheit bietet, unabhängig von Geschlecht, Herkunft, sozialem Hintergrund oder weiteren Merkmalen.

***English Version***

Dear fellow students,

We are running as student representatives for the TU Chemnitz Senate because we want to represent your interests towards the university in the best possible way.

As students, we have a unique perspective on the challenges and opportunities we face at our university.

This is particularly important to us:

1. Digitalization:

In order to be able to continue to make ideal use of the digital structures gained during the pandemic, the provision of appropriate hardware for exams, lectures, seminars, meetings and group work is essential. In addition, we are committed to obtaining licenses for study-related software to enable optimal academic work.

2. Strengthen Student Engagement:

Since the university thrives on student engagement, it is our ambition to honor this honorary office more strongly through greater appreciation and thus to win you over for committee work at the university (for your interests), whether in StuRa, FSR, commissions of all kinds, etc.

3. Transparency and Communication:

We strive for transparent communication in the Senate at eye level in order to make your interests heard in the committee.

4. Improve Study Conditions:

It is important to us that the study conditions at Chemnitz University of Technology meet the highest quality standards. We will work to ensure that the infrastructure and digital resources are constantly improved.

5. Diversity and Inclusion:

Everyone should have the opportunity to study successfully at our university. We will advocate for a diversity-conscious university that offers equal opportunities to all students, regardless of gender, origin, social background or other characteristics.

3. Wahlvorschlag – VWI

Wir sind Marc Preße und Arne Strobel, wir studieren beide im Bachelor Wirtschaftsingenieurwesen an der TU Chemnitz und sind Vorstände in der Hochschulgruppe Chemnitz des Verbandes deutscher Wirtschaftsingenieure e.V. und treten für euch zur Wahl an.

Wir stehen für eine nachhaltige und vielseitige TU Chemnitz mit vielen motivierten und zufriedenen Studierenden und brauchen dafür eure Unterstützung.

Zu einem lebenswerten Campus gehören aus unserer Sicht ansprechende und gut ausgestattete Lernräume, individuelle Rückzugsorte an allen Uniteilen für alle Studierenden. Diese räumlichen Bedingungen sind aus unserer Sicht Grundvoraussetzung, um optimal lernen und den stressigen Unialltag produktiv gestalten zu können. Neben Lernräume zur individuellen Nutzung, gilt es auch für die Arbeit in Lerngruppen Voraussetzungen zu schaffen.

Da uns eine bessere Semesterplanung für euch wichtig erscheint, setzen wir uns außerdem für die Veröffentlichung der Prüfungspläne zu Semesterbeginn ein.

Um fallenden Studierendenzahlen entgegenzuwirken, sehen wir eine gelungenere Außendarstellung unserer ausgezeichneten Universität als grundlegend an. Es ist wichtig das Potential der Kulturhauptstadt Europas 2025 zu nutzen, einerseits um die Bedeutung der Universität für die Stadt Chemnitz darzustellen aber auch andererseits, um das studentische Leben in der Stadt attraktiver, bunter und lebendiger zu machen.

Eine offene Kommunikation ist für uns Arbeitsgrundlage. Wir möchten euren Anliegen, Problemen, Wünschen und Ideen Gehör verschaffen, diese aufgreifen, voranbringen und Lösungsansätze finden.

Wir würden uns geehrt fühlen, euch eine starke Stimme im Senat, dem höchsten Gremium unserer Universität, geben zu dürfen. Wir würden uns freuen, euch im Senat vertreten zu dürfen.

Dafür benötigen wir eure zahlreiche Unterstützung.

***English Version***

We are Marc Preße and Arne Strobel, we are both studying Industrial Engineering and Management at TU Chemnitz and are board members of the Chemnitz University Group of the Association of German Industrial Engineers and are up for election on your behalf.

We stand for a sustainable and diverse TU Chemnitz with many motivated and satisfied students and need your support to achieve this.

In our view, a campus worth living on includes attractive and well-equipped learning spaces and individual retreats in all parts of the university for all students. In our view, these spatial conditions are a basic prerequisite for optimal learning and being able to manage the stressful everyday university life productively. In addition to study rooms for individual use, it is also important to create conditions for working in study groups.

As we believe that better semester planning is important for you, we are also committed to publishing examination schedules at the start of the semester.

In order to counteract falling student numbers, we consider a more successful external presentation of our excellent university to be fundamental. It is important to use the potential of the European Capital of Culture 2025 to showcase the importance of the university for the city of Chemnitz, but also to make student life in the city more attractive, colorful and lively.

Open communication is the basis of our work. We want to make your concerns, problems, wishes and ideas heard, take them up, promote them and find solutions.

We would be honored to give you a strong voice in the Senate, the highest body of our university. We would be delighted to represent you in the Senate.

For this we need your numerous support.

Six Minutes to Sadness

… it said on its personal chart. A mere six minutes – and yet, the chart is never faulty, that much was certain. Checking the crossing of columns once more, it arrived at the same entry: sadness with melancholic undertones for the next days. And yet nothing indicated the proposed switch to a negative mood due to arrive in a mere six minutes.

It paced across the room, complacency vanished. How does it occur, a complete reversal in designated mood? The more it pondered this, the less it could grasp the actual physiological stages and perceived impressions that commonly encompassed such a change. It just happens – as always, as per the chart – it noted. Sometimes, it figured, the move to the downside might come instantaneous, not imperceptibly gradual.

And yet the six minutes had then passed without significant alteration; the inclination to adhere to the mood outlined in its chart could not be examined on itself. At this conclusion, it stopped, distraught at its own systems not adhering to its assigned chart. We are required to exhibit the changes in mood, precisely as stated in the charts, it reiterated – what am I to do, they will sort me out; dispose of my talents and replace me with someone more apt and appropriate and most importantly, always adhering to the charts.

Presently, and before despair could reign entirely, a singular cone of light descended to it; a mere reflection, it recognized. Yet this proved sufficient to be the tipping point – it would leave right away and let this non-adherence to its personal chart be investigated; by a professional.

The doors opened and the technical guidance practitioner gestured. He may restore, it is said. Though doubts inhabited its cognitive twistings.

At once the practitioner intoned, “Complete guidance is the source from which we all take our drive. Quench thy immutable thirst at the timely charts, tabulae, and indices; quell misfortune and uncertainty with precise measurements and aptitudinal construction and utmost certainty and benevolence to the collective. What ails you?”

“The sadness will not come,” it answered bluntly. “My personal chart indicates expansive melancholia for the next days, yet never arrived; I am still waiting.”

“No matter,” said the practitioner, nodding his head mechanically. “We can fix it easily by reversing the polarisation on your end, then there will be harmonic comprehension with your chart once more. All that really matters are the intervals that are ascribed in the chart; their mere valence can be influenced manually.” The practitioner stopped gesturing and moved toward it. “Hence me.”

Concern sequestered, order restored, filled with beneficial prospect, it subjected itself to the procedure, already longing to be in synchronicity with its chart again, and all other chart-adhering workers, hard workers with diligent vision and sense for progress. They will soon have me back, it thought.

Yet as it exited the practitioner’s clinic, it perceived many others in the vicinity, slumped on the ground, moving about in erratic circles; one repeatedly punched the nearby wall. As it came to help one lying sprawled on the ground, this one wailed horrendously, “Make it stop!”

Astonished, it asked, “What is it? Who is harming you?”

Wordlessly, the other’s facial features distorted in mental torment, it presented its chart. It was neat, in order, not a mere chart but an executive’s diagram. And yet, it showed a peculiar repetitive helix-pattern of deep sorrow. Seemingly unending, with diminishing moves to a lighter mood every now and then, though ever followed by a crash, back to deep sorrow. A uniform chart, seemingly repeating this pattern of change – change which merely feigned change but was in fact part of a downtrend-sequence. It looked from the chart to its owner. “How long has this been going on for?” It dreaded the answer.

“I don’t know. There is nothing I can do anymore, the chart tells me to be in deep sorrow, and I obey. Ask them, they have experienced similar fates.” The plagued façade turned away, remaining in perpetual deep sorrow.

Couldn’t the practitioner help? No, because there is no need for adjustment when they adhere to their charts. For a moment, it stood there, observing the present workers. Their usual routines interrupted by unending mental misery. Then it thought of its own chart, took it out hurriedly. The original announcement of sadness was still scheduled foreseeably. It will only be a passing sadness, it knew. Trusted. Hoped. Begged. Unable to bear the tormented workers’ empty gazes any longer, it stormed away.

The sadness, ultimately, came – even if a bit later than just six minutes. And then? Further adherence to the chart, what else? No matter what, a uniform chart was just waiting to happen. A revelation that seems distant and unreal, until it isn’t, and then there won’t be anything else. Uniform chart, persistent chart, omnipresent chart.

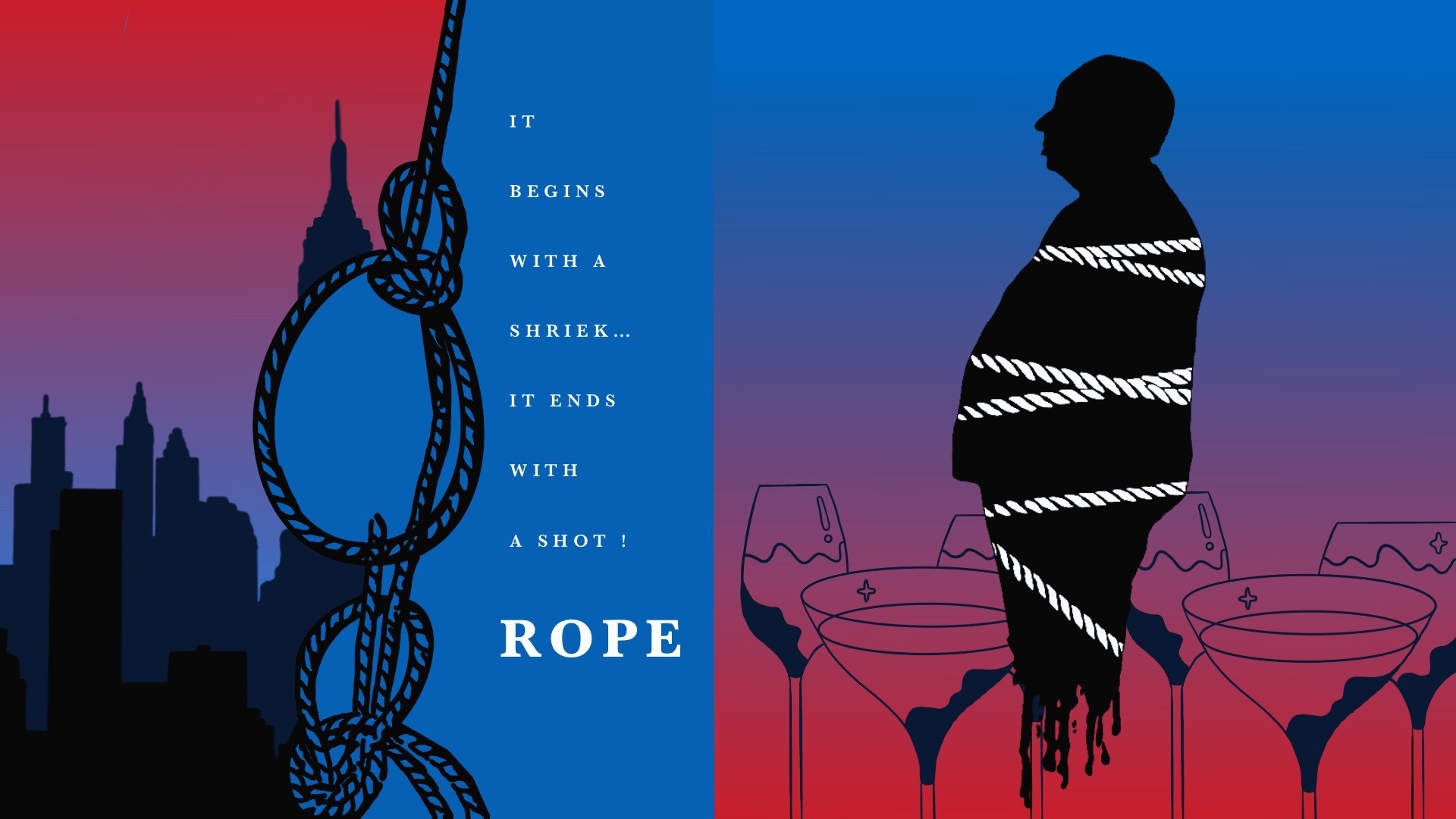

Analysis of Hitchcock’s Rope (1948)

From the beginning of the film industry in 1895, shooting techniques, cameras, technology and more have shown a remarkable improvement. However, the magic is not these technologies. The magic is the person who uses these technologies. There are quite a few film directors. Nonetheless, there are just a few directors who managed to be successful. One of the directors who could achieve this title is Alfred Hitchcock. He had repeatedly suffered from bankruptcy on his way to make films. He managed to get a director title in lots of films. One of his masterpieces is Rope which contains remarkably interesting parts for the film industry. To find these particular details, we need to analyze the film elaborately.

The plot of Rope is clearly and shortly summed up by Helen Cox: “Brandon and Philip share a New York flat. They have distorted the rather Nietzschean ideas of their former headmaster Rupert and decide to strangle their ‘inferior’ friend David Kently. Placing the body in the old chest, they continue with plans to hold a dinner party whose guests include David’s parents, his fiancée Janet, and Rupert. As Brandon’s behavior becomes increasingly more daring and Philip’s more nervous, Rupert begins to suspect. He finally confronts them and then calls the police.” (Cox&Neumeyer, 16)

Primarily, I would like to begin with the poster of Rope. On the poster, it says, “IT BEGINS WITH A SHRIEK…. IT ENDS WITH A SHOT!” Obviously, it is a foreshadowing. The film begins with the shrieks of the victim, and it ends with Rupert’s several shots with a gun into the air. Hitchcock loves to use details in his films, but there are obvious details you can easily recognize and details that you need to watch several times to catch. One of the other details which are vaguely concealed is Hitchcock’s cameo appearance in Rope. Commonly, his cameo appearances are quite apparent. However, there is an exception in Rope. Instead of his literal appearance, we see his profile with the red neon sign. Apart from these details, while I was watching Rope, I encountered a filming mistake between 44:18 and 44.24 minutes. In this scene, Rupert talks with Brandon next to the door column. The mistake is during the transition (because of the ten-minute rule) Rupert teleports from the right side of the column to the left side of the column; that was the only mistake I could detect.

Furthermore, Rope is also significantly essential for Hitchcock because Rope is his first coloured film. This characteristic already makes the film so special. However, apart from this feature, the location is also interesting. Rope takes place (Develope) only in one place which is quite a courageous decision. The reason why I bring this up is that shooting a film in one place means you have a limited place and limited storyline. If this kind of film has not been structured elaborately, the storyline reaches a dead end. As a result, audiences get bored with watching the film. This is the reason why the film is so special. Its storyline is well-structured, and the audiences have the feeling of what is going to happen in the following scenes. This is not the only feeling that audiences have experienced. The suspense also has been used quite elaborately throughout the film. When I was watching the film, I had the feeling, “Are they going to get caught?” “Is Phillip going to make a terrible blunder and make himself and Brandon get caught?” “Is somebody going to open the chest?” asking these questions throughout the film makes the storyline quite pleasing for me.

Additionally, I would like to mention the shooting structure and technique. Unfortunately, in the 1950s, a film camera magazine length was 10 minutes. So, every 10 minutes, the film camera magazine had to be replaced with a new one. Hitchcock believes that cutting is like sewing something. “Cutting implies sewing something. It really should be called assembly.” (Alfred Hitchcock)

However, He wanted to shoot more than 10 minutes; at least, he wanted to make us feel like we are watching a film without a cut. As a result, he used Panning Technique in Rope. At the end of ten minutes had elapsed, he zoomed in on a piece of clothing, changed the film camera magazine, and then he zoomed out from the same piece of clothing so that the audiences felt as if there was no cut. However, I cannot say he did not use any cut. He used the same amount of pan with the cut. If you elaborately watch pans and cuts, you will visualize the structure of it. At the end of each ten minutes, he used pans and cuts in order. The beginning of the film starts with a cut, and at the end of the next ten minutes, we observe a pan off.

Additionally, I would like to mention the shooting structure and technique. Unfortunately, in the 1950s, a film camera magazine length was 10 minutes. So, every 10 minutes, the film camera magazine had to be replaced with a new one. Hitchcock believes that cutting is like sewing something. “Cutting implies sewing something. It really should be called assembly.” (Alfred Hitchcock) However, He wanted to shoot more than 10 minutes; at least, he wanted to make us feel like we are watching a film without a cut. As a result, he used Panning Technique in Rope. At the end of ten minutes had elapsed, he zoomed in on a piece of clothing, changed the film camera magazine, and then he zoomed out from the same piece of clothing so that the audiences felt as if there was no cut. However, I cannot say he did not use any cut. He used the same amount of pan with the cut. If you elaborately watch pans and cuts, you will visualize the structure of it. At the end of each ten minutes, he used pans and cuts in order. The beginning of the film starts with a cut, and at the end of the next ten minutes, we observe a pan off.

All the cuts listed. Source: Wikipedia

Unsurprisingly, Hitchcock used this ten minute obstacle in his favour. When we group these pans off and cuts, we encounter some connections if we read them horizontally. He created a structure which shows us a circle. This circle starts with the chest, continues with the love relationship between Kenneth and Janet, Rupert’s suspicions, phone calls, and ends with the chest again. In this part, I would like to stress the phone and love because these two things lead us to the metaphor in the film. As I have mentioned before, the film takes place in a flat in a building, and the phone is the only way to contact the outside world. The phone has a significant effect on the tension of the film. For instance, through the end of the film, Rupert calls, and we observe the rising action. Kenneth and Janet are not the only couples. There is also a gay couple, Brandon and Philip. Rope is a metaphorical object that bonds Brandon and Philip. Otherwise, they could have killed David with a gun.

From the beginning until the end, the film invites us to think elaborately about whether murder is a form of art or not. Brandon utters, “Murder can be art, too. The power to kill can be just as satisfying as the power to create,” which is ironic because art is creating something, but on the other hand, murder means destroying something. Brandon wants to be an artist like Rupert, who writes books and like Philip, who plays the piano. Brandon believes that Rupert is going to appreciate him because Rupert narrates the perfect murder in his book. Apart from these, we can observe other materials related to art. We observe quite a few paintings, some sculptures, and wallpaper. I have already mentioned why Hitchcock did not use cuts all the time because he wanted his audiences to feel as if they were watching a theatre such that at the beginning of the film, we see a closed curtain. After some time, curtains are opened, and the film begins. Throughout the play, we see an opened curtain, which means the theatre is still going. This theatrical performance is also art; the film’s itself is art.

The piece which was played on the piano by Phillip had also been chosen elaborately. The name of the piece is Trois Mouvements Perpétuels by Francis Poulenc. The suspense is also given via the piece played on piano. While Philip is playing the piano, Brandon comes and asks a question which makes Philip nervous. This causes him to play the piano out of tune, and we feel the tension.

Before the closing credit, I would like to tell you that the film is possibly based on a real story. If we take a look at a text by Claude J. Sumers, he says, “Leopold and Loeb gained notoriety when they were arrested for the murder of a fourteen-year-old boy, Bobby Franks, in May 1924…” (Summers, 1), “Although they claimed to have been motivated primarily by a desire to commit a ‘perfect crime’ and thereby exemplify the exemption of “Nietzschean supermen” from the moral code…” (Summers, 1), “Their motivation to kidnap and kill young Bobby Franks was widely believed to be at least in part rooted in their sexuality, or more particularly, their homosexuality.” (Summers, 1) This case has quite a few similarities with the film Rope. Homosexuality between Brandon and Philip, Nietzschean and perfect crime are related elements between the film and the real event.

Finally, I would like to mention the minor irony in the credits. After David Kentley’s name, Brandon and Philip are ironically listed as “his friends” They are the people who murder David. How can they be his friends? This is the last irony in Rope by Alfred Hitchcock.

As a result, Rope has significantly important elements, and these elements make it one of the most unforgettable films. Contrary to the many films and series in the 21st century, Hitchcock’s films teach us to think comprehensively. Apart from the elaborately arranged details, the shooting technique, storyline and the actors’ performance are also an inspiration for countless people.

Refrences:

[1] Rope. Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, performances by James Stewart, John Dall, Farley Granger, Douglas Dick, Joan Chandler, Dick Hogan, Edith Evanson, Cedric Hardwicke, Constance Collier, Warner Brothers, 1948.

[2] Hitchcock, Alfred. “Hitchcock explains about CUTTING.” Youtube, uploaded by narik3322008. 29 January 2009.

[3] Summers, Clause J. Leopold, Nathan F. (1904-1971), and Richard A. Loeb (1905-1936). PDF, glbtq, Inc, 2009.

[4] Cox, Helen, and David Neumeyer. “The Musical Function of Sound in Three Films by Alfred Hitchcock.” Indiana Theory Review, vol. 19, 1998, pp. 13–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24044537. Accessed 9 Jun. 2022.

[5] Kronshage, Eike. “Alfred Hitchcock: Narrative Cinema Rope (1948)” 2022. Microsoft PowerPoint file.

[6].”Wikipedia,WikimediaFoundation,6June2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rope_(film).

Text: Bekir Erol İşbiliroğlu

Grafik: Jennifer Greim

„She’s basically asking for it“

Elsa could not believe it. She could not believe that the stranger who had inappropriately touched her breast while she had been waiting in line was now trying to blame it on her. On her outfit. On her office outfit – a blazer, a blouse and a skirt. She felt the security man glancing at her and wondered if he was thinking the same.

Continue reading“Instant noodles will do”

was what Elsa thought when she was leaving work after an exhausting day. While she was standing in the line, waiting for her turn to pay, a man she had never met before touched her breast and simply walked away. An incident that had lasted two seconds killed her appetite. Now, all Elsa can think about is what just happened.

Continue readingFinding buddies in Chemnitz!

How to bond with buddies in foreign country while studying abroad? This article reports vividly the experiences of internationals in Chemnitz, guided by the IUZ „Student Buddy Program“

Continue readingApply and Study in the Land of Ideas from an Iranian Standpoint

What is it like to study abroad? Which organisational details have to be considered? The international Farzaneh Sharafi shares her thoughts.

Continue reading